Over/Under 1: 21st Century Schizoid Band

March 3, 2018

(In which we take a look at the overrated OK Computer and the underrated Parklife)

Looking back at the turn of the millennium is a strange thing to do. The digital revolution, poised to usher in a futuristic new era of civilization, was met with ambivalence by many young people. Raised in the post-idealistic latter half of the 20th century, Gen-Xers entered the 1990s with a profound disaffection for the institutions that dominated their lives. This outlook played a big part in influencing the pop cultural landscape; instead of the smug neoliberalism and hawkish nationalism of the 80s, mainstream media of the 90s pivoted to reflect the ennui of modern life. Of course, it seems almost quaint now to think about a time before the War on Terror and the financial crisis. The 24-hour news cycle did not yet exist to terrorize geriatrics and exacerbate everyone’s neuroses. With widespread globalization and technological expansion still just over the horizon, the 90s marked the last vestiges of a life unplugged. And yet at the time, some were already feeling a growing sense of discomfort.

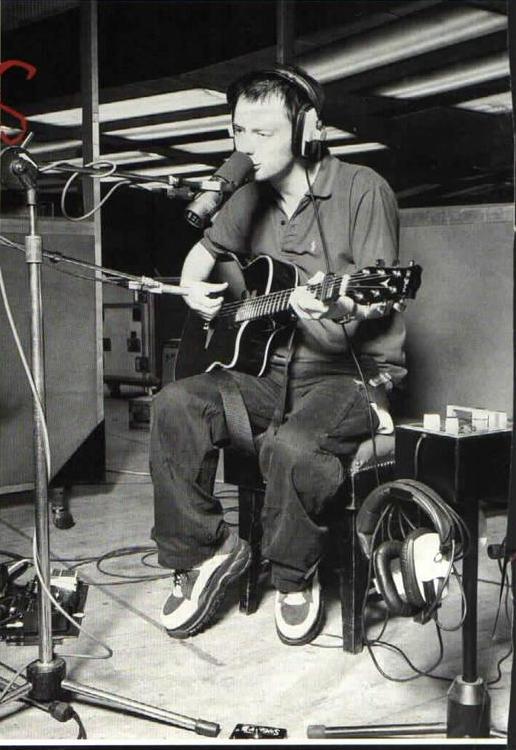

Soon after the Reagan years came to an end, so did the Thatcherite reign across the pond. Many popular English musicians held similarly cynical views on the trappings of modern life and where the world was headed. Thom Yorke was one such person. During the recording process of Radiohead’s third album in 1996, the band was forced by their label to go on tour, opening for Alanis Morissette. The burden of touring was particularly draining for Yorke and ultimately pushed him into a dissociative state. He began drawing cars and airplanes and escalators on hotel stationery and scrawling fragmented lyrics like, “I’m trying to get some rest / From all the unborn chicken voices in my head.” The world around him was simply moving too fast; according to Yorke, songwriting was his way of “trying to reconnect with other human beings when you’re always in transit.”

These deep-seated feelings of purposelessness and alienation became the framework for OK Computer, Radiohead’s subversive art-rock opus, widely considered to be a masterpiece. To their credit, the album is a bold and uncompromising statement that somehow captured the bleak paranoia of the early aughts before it ever happened. But Yorke might have said it best himself: “Lighten the f*ck up.Û

Although their previous album had its fair share of memorable hooks, Radiohead was never really a Britpop band. They didn’t much care about making commercially successful or easily digestible music in the same vein as Oasis or Blur. While their ambition is admirable, there’s something to be said for taking complex, heavy ideas and making accessible art. Maybe they could’ve learned something from their pop-oriented counterparts.

Despite often garnering comparisons to Oasis, Blur’s artistic trajectory more closely mirrors that of Yorke and crew. After a forgettable debut album and a promising follow up, Blur released Parklife in 1994. Although its predecessor (1993’s Modern Life is Rubbish) demonstrated frontman Damon Albarn’s gift for wry observational lyricism, Parklife is simply made with sharper versions of the same tools. Over 16 tracks, Albarn crafts a subtly incisive critique of working class drudgery, materialistic culture, and undue nationalism. He owes a great deal of debt to the Kinks’ Ray Davies, who knew a thing or two about singing the tongue-in-cheek praises of English life and culture. Davies is widely celebrated as a lyricist for his eloquence and nuance; he’d mock outdated English traditions while simultaneously criticizing all the new skyscrapers popping up. Albarn’s writing on Parklife is smartly informed by this unpretentious approach to writing. Yes the world is changing, he seems to argue, so let’s address what exactly is going to shit. In the chorus of late single “End of a CenturyÛ, Albarn sings,

“We all say, don’t want to be aloneWe wear the same clothes ’cause we feel the sameWe kiss with dry lips when we say goodnightEnd of a century, oh, it’s nothing specialÛ

It’s not that he feels radically different than Thom Yorke did just a few years later. But rather than bury those feelings under four layers of spring reverb and a distortion pedal, Albarn and his bandmates are candid with their apathy. This transparency (or lack thereof) is apparent in the sonic backdrop of both albums. Blur wears their influences on their sleeve; deadpan wit from the Kinks is complemented by the jangly guitar tone of early Who records and the frenetically poppy hooks of XTC’s best work. The inclusion of songs like the brass-heavy waltz The Debt Collector and the disco-indebted Girls and Boys demonstrate Blur’s broad artistic range as well as their willingness to be just subversive as Radiohead (if not necessarily as cryptic). Radiohead, of course, is less overt in incorporating their inspiration. Much like Yorke’s fragmented lyrical style, we can only ever catch glimpses of familiarity. The album’s title comes from Douglas Adams’ TheHitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy; much of Yorke’s lyrical inspiration came from reading Noam Chomsky; they sought to recreate the dense harmonic deconstruction of Bitches Brew-era Miles Davis through the unconventional production style of krautrock and atonal 20th century composition. In what would prove to be a defining characteristic of Radiohead’s sound, they cast a wide-but-shallow net; even guitarist Johnny Greenwood said the album really came about as a product of being “in love with all these brilliant records…trying to recreate them, and missing.Û

Maybe that’s where I lose interest. Throughout their discography, but especially here, Radiohead feels like a group of smart musicians playing in a postmodern jam band. There’s extended string techniques and harsh synths and crunchy layered guitars, but the end product ultimately feels unengaging. Famously innovative bands like the Beatles and the Beach Boys succeeded because they could masterfully balance harmonic innovation with accessibility. You can recognize a Paul McCartney melody or believe the pain in Brian Wilson’s voice after just a note or two. They left their legacy on popular music without feeling the need to be overly elusive or self-serious. Blur also excels at this; Damon Albarn’s messages come across clear and strong, but never at the cost of sacrificing an engaging musical moment. The music is elevated by its wit and carried by its craft, rather than just its scope.

Arguably, OK Computer and Parklife are the two definitive British albums of the decade. At the very least, they capture the sociopolitical climate of the 90s with a clarity that stands the test of time. Kashana Cauley once postured the Strokes’ Is This It and Arcade Fire’s The Suburbs as urban malaise versus suburban ennui. This distinction applies here too, with Radiohead’s metropolitan claustrophobia against Blur’s village green pseudo-idyllia. Both artists take their respective brand of jaded cynicism and use it to create a statement album so inextricably tied to its time. Though the latternever found the same acclaim outside of the UK (and to be fair, neither did Blur), the formeris a stalwart contender on every major publication’s “Best Albums” list. It certainly carved out its legacy in rock music; critics seemingly cannot overstate the influence of OK Computer (and its follow up Kid A) on our public consciousness as the shadow of the 21st century crept up. While I admire the sentiment, I can’t help but think that even if Radiohead dialed down the melodrama, we still would have figured out how to disappear completely.